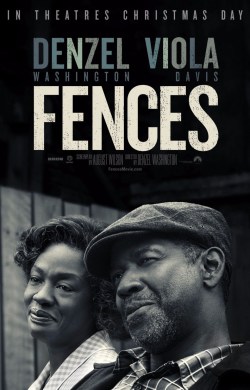

Fences

August Wilson doesn’t get the popular respect he deserves. His plays easily merit a place alongside Arthur Miller and Edward Albee in the canon, but I admit I hadn’t read any as I was growing up. And this year has been marked by repeated realizations just how exceptional and progressive my public school education was.

Denzel Washington means to rectify that omission. He’s been entrusted by Wilson’s estate to bring the entire Century Cycle to screens big and small over the next decade, starting by helming a theatrical release of Fences himself. If this one is any indication, we’re set for ten years of serious contenders for Best Picture awards.

Set in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, like most of the Cycle’s plays, Fences watches a working-class Black family in the 1950s. Troy Maxson (Washington) is a garbage collector who starts the play complaining to his friend Jim Bono (Stephen McKinley Henderson) about how only white workers are eligible for positions driving the trucks, and they’re stuck with the lower-paying and less pleasant job swinging cans in the back.

But this slips away soon enough. It’s payday, after all, and Troy and Bono pass a flask back and forth as they walk into Troy’s backyard, Troy showing off his gift of storytelling gab as they’re joined alternately by his wife, Rose (Viola Davis), his son from a previous marriage, Lyons (Russell Hornsby), and his brother, Gabe (Mykelti Williamson). Troy and Rose’s son, Cory (Jovan Adepo), won’t show up until after football practice, the next day.

Washington seems to have fallen into the same niche as Robert De Niro. He’s a great actor, but it’s been easy to forget that lately with the roles he’s taken. It’s impossible to forget here, with some of the best character work this year that should put him in strong contention for awards this season. Troy is a difficult, complicated man. He’s hard, and even sometimes cruel towards his sons. He flirts with other women, and justifies it to himself by how he works for the family he has built. He’s selfish, unable to recognize the needs of those around him. He’s fun and charismatic, as long as he’s getting his way as the center of attention.

Wilson’s genius in writing Troy — in both the original play and its light adaptation to the screen which he completed before his death in 2005 — was to also show us where Troy came from. How he hated his father, who he resembles more closely than he wants to admit. How he struggled and felt cheated through his life, so he guards what he has jealously and tries to harden his boy against similar treatment. We can see him as both a domineering villain and a tragic figure equal to Willy Loman.

It takes a strong woman to stand up to such an outsized character, and Davis is more than capable of playing the part. I wish Rose had been given a comparable depth to her husband, but she has an important role to play as the matriarch who holds the family together when paternal authority breaks down.

The rest of the cast are all at the tops of their games. Williamson plays the injured Gabe with a sensitivity that far exceeds the near-cartoonish Bubba from Forrest Gump. Henderson is more than capable of playing Bono as a necessary counterweight to Troy, which you might never guess from the cheap bit parts that mainstream fare keeps allotting him, not to mention this year’s own indie darling Manchester By the Sea. Hornsby delivers the same solid, workmanlike performance that he exhibits in one role after another. And Adepo builds on his career’s solid start in The Leftovers, produced by the same HBO that’s working with Washington on the rest of the Century Cycle.

And it’s Washington behind the camera that brings them all together and realizes Wilson’s vision so powerfully. He’s helped in no small measure by his choice of Far From the Madding Crowd cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen, who turns the light itself into an essential part of the scene. Each shot is framed beautifully, and the camera moves with a care and precision that are all but lost in today’s dominant hand-held, shaky aesthetic. This is a film that knows it has something worth saying, and doesn’t need to assault the audience with cheap gimmickry.

Fences is a late entry into this prestige season, and it seems to come out of nowhere, with no festival-circuit drumbeat announcing its arrival. It doesn’t need one, though. It speaks for itself, calmly and simply, with a story that we’ve heard a thousand times, but which becomes as fresh and vital as ever by casting it into a setting the guardians of the literary canon all too often overlook.

Worth It: yes.

Bechdel-Wallace Test: fail.

Trackbacks