Closed Circuit

London has something on the order of half a million closed-circuit television cameras pointed at various places all around the city, many of which are networked and monitored by various authorities. This is, as you might expect, a nightmare for privacy advocates and skeptics of untrammeled government authority. You might also expect a British legal thriller titled Closed Circuit to mount an indictment of the surveillance state, or even to concern itself with this issue in the slightest. If so, you would be as sadly disappointed as I was.

Instead we have an unimaginative potboiler that barely reaches a simmer. In the aftermath of a terrorist bombing in the heart of London the police round up their suspect and the Attorney General (Jim Broadbent) prepares for a partially-secret trial. There is little time spent on explaining just how such a trial is supposed to work — some clearer exposition at the outset might help in a cross-examination of the concept — but what we gather is that in addition to a barrister, the defense will be appointed a special counsel who is cleared to examine the secret evidence in closed court sessions, but who for some handwaving reason is not supposed to have any contact with the defense barrister after actually seeing any secret evidence. How, exactly, this setup manages to even appear to support both goals of government secrecy and a credible defense is far from clear, but I get the feeling screenwriter Steven Knight didn’t really spend too much time thinking about making this actually plausible.

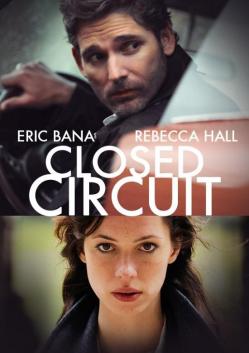

Six months on, the original barrister commits suicide, and the defendant’s solicitor (Ciarán Hinds) enlists Martin Rose (Eric Bana) to replace him. The catch, though, is that Rose has had an affair with the special counsel, Claudia Simmons-Howe (Rebecca Hall), which is evidently against some sort of rule. Again, we’re asked to swallow a huge chunk of setup just because, with no real reasoning behind it. This is even more awkward here, since the whole post-romantic subplot is haphazardly executed, and is totally unnecessary to the rest of the story.

Anyway, it quickly becomes clear that there’s more to this case than meets the eye. There’s a creepy British intelligence agent running around (Riz Ahmed), and a journalist (Julia Stiles) trying to contact Martin who never really adds anything beyond some spooky “They Are Watching Everything” boilerplate. And it all degenerates pretty much as you’d expect.

The thing of it is, there are real problems inherent to a surveillance state with an expansive notion of secret power in the name of national security, and this film engages it in the laziest possible way. Just quoting the idea of shadowy, secretive government figures is not the same as making an argument against government secrecy. The story never seriously interrogates the notion of secret trials; we’re meant to already believe that they’re wrong and then have that belief justified by something going wrong in parallel with one. But nowhere is even this thumbnail sketch of a secret trial system shown to be structurally unsound. Nowhere do we see a real case that secret trials — even just this one cartoonish version — are fundamentally incompatible with justice.

And this is all on top of the fact that the movie is itself misleading from the start. If it never makes a serious case against secret trials, it never really engages with the problems of London’s culture of surveillance at all, despite that being the clear referent of the title. There’s even a line highlighted in the trailer about the ubiquity of closed-circuit cameras, which then does not actually appear in the movie itself.

Yes, director John Crowley uses the recurring motif of a bank of CCTV displays as a stylistic trope, but there’s never a sense that anyone but us is watching these images. When we see eight different angles on the same scene, each helpfully labeled with a camera ID and running timestamp, we’re meant to think of some sinister agents monitoring the action, but we never actually pull back to see who they are so the story can cross-examine them. If the motto of surveillance-state opponents is quis custodiet ipsos custodes? — “who watches the watchmen?” — it seems that Crowley and Knight are content to answer, “no one does”. They certainly aren’t interested in doing the job, even as they try to play on our sense that maybe someone should.

Worth It: no.

Bechdel Test: fail.